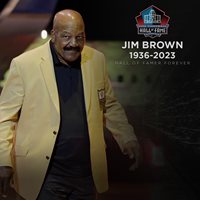

Football's 'greatest player,' Jim Brown: 1934-2023

Hall of Famer Forever

Published on : 5/19/2023

The football world today is celebrating the life and career of JIM BROWN,(Opens in a new window) the Cleveland Browns fullback whom many considered the greatest athlete to play professional football.

The football world today is celebrating the life and career of JIM BROWN,(Opens in a new window) the Cleveland Browns fullback whom many considered the greatest athlete to play professional football.A member of the Pro Football Hall of Fame elected in his first year of eligibility, 1971, Brown died Thursday night at age 87.

“Nobody ever ran with a football like James Nathaniel Brown,” legendary Los Angeles Times sports columnist Jim Murray wrote. “Jim Brown wasn’t a player; he was a Force.”

“When Jim Brown’s name was announced in a room, other Hall of Famers stood and applauded him,” said Pro Football Hall of Fame President Jim Porter. “His persona has stood the test of time — a fearless and dominant football player. Jim will always be remembered as one of pro football’s greatest individuals.

"Our thoughts and prayers are with Jim’s wife, Monique, and their entire family. The Hall of Fame will honor his legacy for years to come."

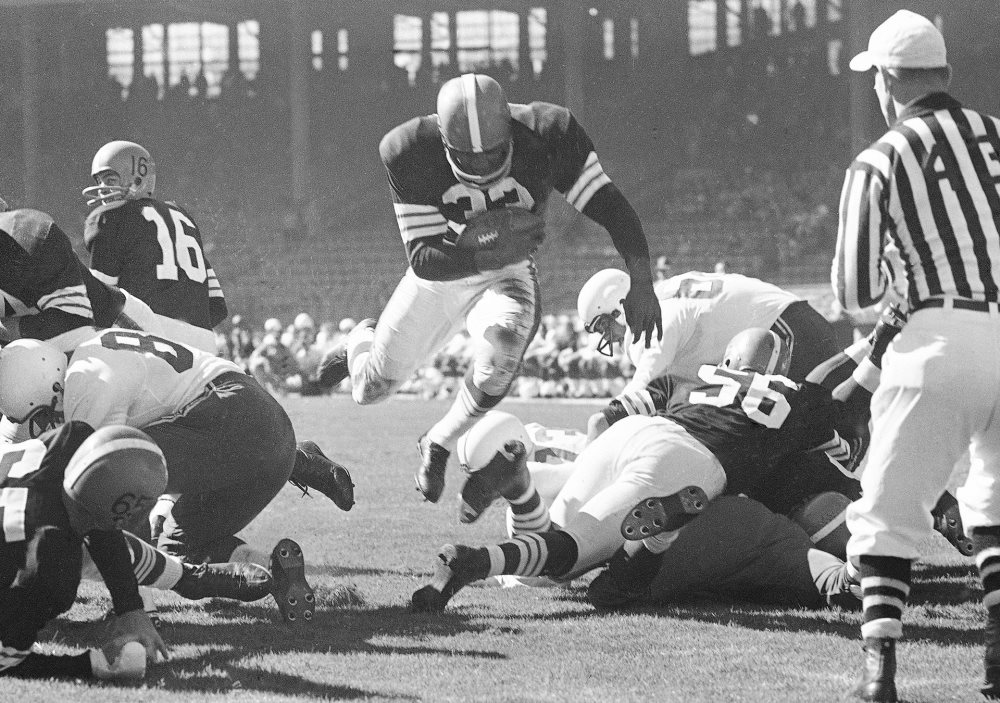

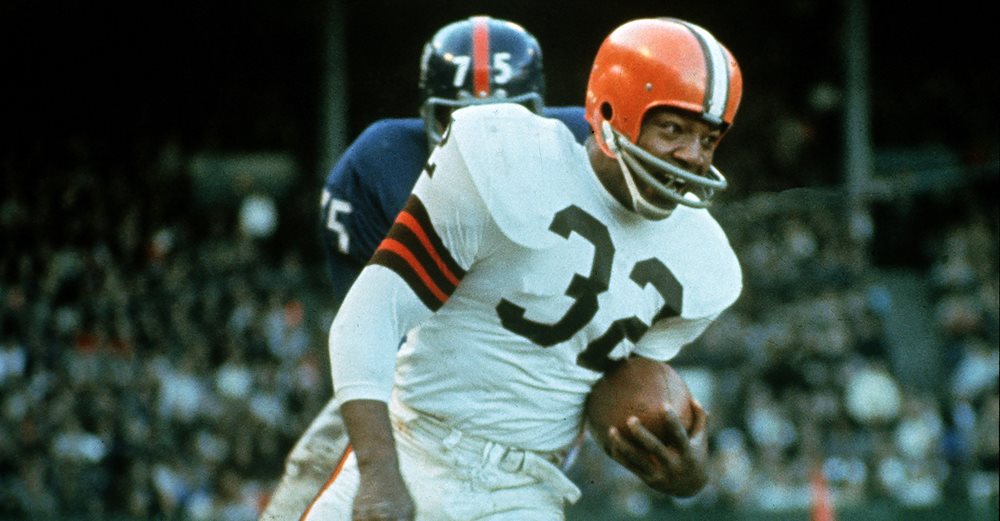

Known for a running style that administered as much punishment as he received, Brown was as durable as he was rugged, playing all 118 games from the season opener in his 1957 rookie year to the season finale in 1965, his last season and arguable his best all-around year in the National Football League.

With 1,872 total yards from scrimmage and 21 touchdowns, Brown earned his third NFL Most Valuable Player Award in 1965. The productivity led many to speculate for more than a half-century how many more accolades and records Brown could have compiled if he hadn’t retired from football prior to the 1966 season.

Playing only nine seasons, Brown held every meaningful rushing record at the time of his retirement. Among the most significant: single-season yards gained (1,863 in 1963), a record that stood for a decade; and records for career yards (12,312 yards) and touchdowns (106) that stood for two decades.

In the ninth game of his rookie season, facing the Los Angeles Rams, Brown ran for 237 yards, an NFL record for 14 seasons. It remained a rookie record for 40 years. He is the only player in NFL history to average more than 100 rushing yards per game for his career (104.3). His 5.2 yards per rush is second-best among players with at least 1,000 carriers.

Brown’s six games with at least four rushing touchdowns and 14 games with at least three rushing TDs remain NFL records.

He was named to the NFL 50th Anniversary All-Time Team, the NFL 75th Anniversary All-Time Team and the NFL 100 All-Time Team. The Sporting News (2002) listed Brown as the greatest player in the history of the NFL. In 2014, the New York Daily News put together a 15-person panel of NFL experts (four who are now Hall of Famers and several who are Hall Selectors) that voted Brown the game’s best player.

“Paul Brown called him the best football player he ever saw,” longtime general manager Bill Polian, a member of that Daily News panel, said then. “I share that opinion.”

Hall of Fame defensive back MEL RENFRO(Opens in a new window) concurred, calling Brown “the greatest running back who ever played the game.”

“I tried to tackle him – hit him as hard as I could – and he just ran right over the top of me,” Renfro told an interviewer. “And a guy that big, nobody ever ran him down from behind.”

Renfro said tackling Brown required three elements: “You hit him and you hold on and you pray for help. I know I did that many times.”

Hall of Fame safety PAUL KRAUSE(Opens in a new window) responded similarly when asked about his on-field encounters with Brown.

“I think I made the tackles,” he said, “but I just hung on and yelled for help. He was the best running back I’ve ever seen in my life or played against in my life.”

All-around athlete

All those accolades for a man who often said football wasn’t his best sport.

Brown spent the first eight years of his life on St. Simons Island, Ga., before moving to Long Island, N.Y., to be reunited with his mother. She had spent several years there working as a domestic to earn money for the family.

At Manhasset (N.Y.) High School, Brown earned 13 varsity letters in football, basketball, baseball, lacrosse and track. He was all-state in football after gaining 14.9 yards per carry in his senior year for an undefeated team, and he averaged 38 points per game in basketball.

He caught the eye of dozens of colleges offering full scholarships but went to Syracuse University as a non-scholarship (unbeknownst to him) player. It was not a good fit at first, with a strong undercurrent of racism against Brown, who was the only Black on the roster. Buried on the depth chart and unhappy, he nearly left the university.

His high school superintendent convinced him to stay, and after that tumultuous freshman year Brown’s talent – 10 varsity letters in football, lacrosse, basketball and track – couldn’t be denied.

As a senior in 1956, he led the nation in rushing touchdowns and gained 986 yards in only eight games. Syracuse earned a berth in the Cotton Bowl, falling to TCU, 28-27, despite 132 rushing yards and 21 points from Brown. At season’s end, he was a unanimous All-America selection and finished fifth in Heisman Trophy voting.

He concluded his collegiate career with 2,091 rushing yards and 26 touchdowns, along with eight interceptions as a defensive back. In a 61-7 victory over Colgate in 1956, he scored 43 points on six touchdowns and seven extra points.

In lacrosse, he was a two-time All-American. As a senior, in the spring of 1957, he scored 64 points and was ranked second in the nation with 43 goals.

In 1984, Brown told the New York Times: “Lacrosse is probably the best sport I ever played.”

Brown was elected to the Lacrosse Hall of Fame, where he remains the only Black athlete inducted. The professional Premier Lacrosse League named its MVP trophy for him.

Inside the Carrier Dome, an 800-square-foot tapestry depicting Brown in football and lacrosse uniforms proclaims him the “Greatest Player Ever.”

In 2020, ESPN concurred, naming him the greatest college football player of all time during a ceremony at the College Football Playoff National Championship Game celebrating the 150th anniversary of college football.

NFL career

The Cleveland Browns selected Brown with the sixth overall pick of the 1957 NFL Draft.

“Coming to Cleveland, Paul Brown, I felt like I’d died and gone to football heaven,” Brown said. Unlike his college experience, he had landed in a situation where two head coaches built the offense around their best player.

Under Paul Brown and his successor, Blanton Collier (starting in 1963), Jim Brown led the NFL in rushing yards eight times, carries six times and touchdowns five times.

“When you’ve got a big gun, why not fire it as often as possible?” Paul Brown once said.

Brown followed his eye-opening rookie season with a second MVP performance in 1958. He obliterated the NFL’s single-season rushing record (Hall of Famer STEVE VAN BUREN'S(Opens in a new window) 1,146 yards in 1949) with 1,527 yards in 12 games. He led the league with 17 rushing touchdowns, nearly doubling the runner-up’s nine.

He followed with three seasons of at least 1,257 rushing yards before he “slumped” to 996 yards in an injury-affected 1962 season. Returning to full health and under the direction of the more player-friendly Collier in 1963, Brown exploded for 1,863 yards and 12 touchdowns, averaging a career-best 133.1 yards per game.

Despite Brown’s staggering productivity, the Browns finished a fifth consecutive season out of the playoffs, and Brown had yet to win a championship. Naysayers began tagging him as incapable of “winning the big game.”

That finally changed in 1964, a magical year in Cleveland. Brown ran for 1,446 yards, and quarterback Frank Ryan threw for 2,404 yards and a league-leading 25 touchdowns. In the 27-0 win over the Baltimore Colts in the NFL Championship Game, Brown carried 27 times for 114 yards, setting up Ryan to connect with game MVP Gary Collins on three scoring passes.

“Unless he wins a championship, even a superstar is never fully accepted,” Brown said. “So it felt good … I said, ‘Self, breathe this in, and don’t be in any rush. You got exacty where you wanted to go.’ In life, that is rare.”

The NFL title stood as the city of Cleveland’s only major sports championship for 52 years and cemented Brown’s legacy with the team’s fans.

Brown, who began contemplating retirement from football before the 1964 championship season, came back for the 1965 season to try to claim back-to-back NFL titles. Vince Lombardi’s Packers dashed the Browns’ hopes, however, limiting Cleveland to 36 offensive snaps in a 23-12 win. Brown forever felt the icy conditions at Lambeau Field played a huge role in determining the outcome; he was held to 50 yards on 12 carries.

Brown was selected to his ninth Pro Bowl following the 1965 season and was named the game’s MVP for a third time. It would be his last professional game.

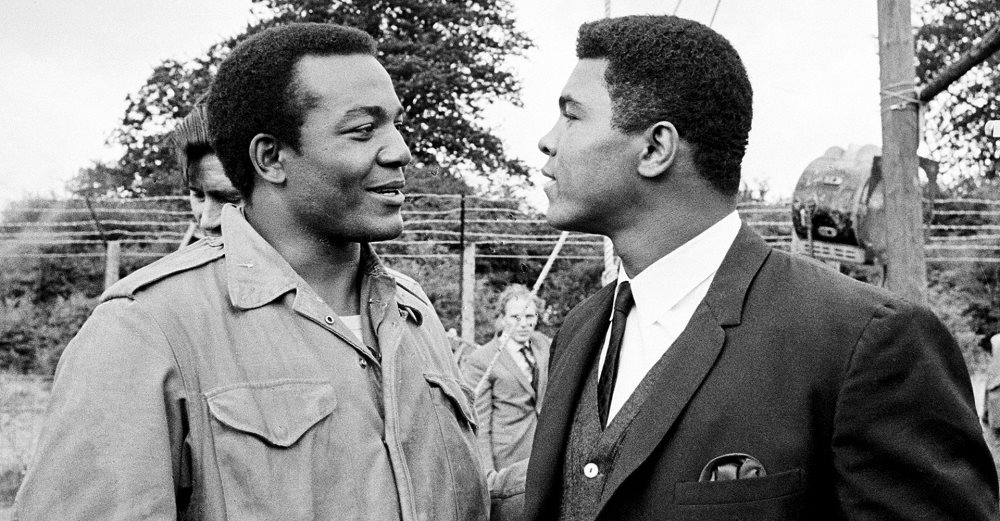

With a movie credit already under his belt, Brown headed to London in the summer of 1966 as part of a star-studded ensemble cast working on the film “The Dirty Dozen.” When the film schedule and training camp schedule collided, the back-and-forth with Browns owner Art Modell became public. Modell’s threat to fine Brown for missing camp ended any chance of luring Brown back to football.

Of the failed attempt to strong-arm him into playing in 1966, Brown said: “Intimidation doesn’t work with me.”

A second career

Goodbye, football; hello, Hollywood.

Brown said he never regretted the decision to walk away from the game at age 29.

“Acting was a challenge unmet, and that intrigued me,” he said. He also made numerous references to how much more pleasant physical contact with leading ladies felt than contact with defense players hell-bent on ending his career even sooner.

Brown’s 53 acting credits included several leading roles in the late 1960s and early 1970s in such films as “Ice Station Zebra,” “100 Rifles” and “El Condor.” Later films included “Any Given Sunday,” “He Got Game” and “Mars Attacks!”

“Hollywood gave me roles that weren’t specifically written for Blacks,” Brown said. “I didn’t plan my career that way, but I understood the significance, albeit temporary, and I enjoyed breaking down some barriers.”

Soon, however, roles became fewer and Brown watched those racial barriers return. Never content to deal with symbolic gains in racial equality, Brown worked for economic parity and Black entrepreneurism, voting rights, increased voter participation and political power through gains in elected offices.

In 1988, Brown founded the Amer-I-Can Program, working with juveniles in gangs in Los Angeles and Cleveland. The program seeks to help enable individuals to meet their academic potential and contribute to society by first lifting their sense of self-worth.

“I don’t think there can be anything more important than keeping young people from killing each other,” Brown said about the efforts to end gang violence. “The approach was to go into the belly of the beast and turn those lives around.”

Brown had his own skirmishes with law enforcement, frequently precipitated by domestic situations. He faced several allegations of physical abuse against women, many unfounded, but not all, and he acknowledged striking some women.

“I don’t think any man should slap a woman,” Brown wrote in his autobiography. “In my case, it’s related to a weakness. … I regret those times.”

On social reform, including minority hiring in the NFL, Brown refused to be silenced, attacking causes in much the same manner as he would an opposing defense: directly and with blunt force.

“I haven’t always been noble or patriotic in my criticism,” he said. “But I have criticized this country, the NFL, certain individuals, because I loved them, felt they needed to be reminded, by someone, of something they had lost.”

The world, far beyond pro football, lost someone special with the passing of James Nathaniel Brown. Social advocate. Voice for the marginalized. Change agent.

“Jim Brown was not principally a great football player,” sociologist Dr. Harry Edwards said in an NFL Films biography of Brown. “Jim Brown was a great man who just also happened to play a great game of football.”

The contributions of that “great man,” to the Game and to society, will be preserved forever at the Pro Football Hall of Fame in Canton, Ohio.

Previous Article

Hall of Fame Class of 2023 member Zach Thomas shares personal message for Canton community

The Pro Football Hall of Fame is honored to present personalized video messages to the Canton community from this year's class.

Next Article

Hall of Fame Class of 2023 member Darrelle Revis shares personal message for Canton community

The Pro Football Hall of Fame is honored to present personalized video messages to the Canton community from this year's class.