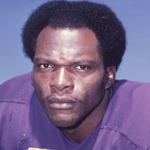

DL / DE

Carl Eller

Class of 2004

First- or second-team All-NFL selections

9

Fumble recoveries

23

Pro Bowls

6

Seasons

16

Unnofficial sacks

133

"I’ve always wanted to be a super ballplayer, always wanted to be a star. I want to be the best in this league, and that’s what I work on.”

Enshrinement Speech

Career Highlights

In 1964, Carl Eller, a consensus All-American with the University of Minnesota, was a first-round draft pick of both the National Football League’s Minnesota Vikings and the Buffalo Bills of the then-rival American Football League. A 6-6, 247-pound defensive stalwart, Eller opted to stay in a familiar environment and signed with the Vikings. For the next 15 years through 1978, he was a fixture in one of pro footballs most effective defensive alignments. He finished his career with one season with the Seattle Seahawks in 1979, having played in 225 regular-season games.

In 1964, Carl Eller, a consensus All-American with the University of Minnesota, was a first-round draft pick of both the National Football League’s Minnesota Vikings and the Buffalo Bills of the then-rival American Football League. A 6-6, 247-pound defensive stalwart, Eller opted to stay in a familiar environment and signed with the Vikings. For the next 15 years through 1978, he was a fixture in one of pro footballs most effective defensive alignments. He finished his career with one season with the Seattle Seahawks in 1979, having played in 225 regular-season games.

During Eller’s career, the Vikings enjoyed great success on the field. Starting in 1968, Eller’s fifth campaign, Minnesota won 10 NFL/NFC Central Division titles in the next 11 seasons. The Vikings won the 1969 NFL championship and NFC crowns in 1973, 1974, and 1976 and played in four Super Bowls.

A major factor in this long string of successes was a ferocious defensive line often referred to as “The Purple People Eaters.” Eller was the left end of a line that included Jim Marshall at the opposite end and Hall of Famer Alan Page and Gary Larsen at the tackles. Extremely quick and mobile for his size, Carl was an excellent defender against the run and superb as a pass rusher. In one three-season string (1975-77), he recorded 44 sacks, according to unofficial statistics. (Sacks did not become an official NFL statistic until 1982). He also was effective in blocking kicks and during his career recovered 23 opponents’ fumbles, the third-best mark in NFL annals at the time of his retirement. It was Eller who caused the fumble that led to teammate Jim Marshall’s infamous wrong-way run for a safety in 1964 in a game against the San Francisco 49ers.

Super-stardom was predicted for Eller from his first day in training camp following the 1964 College All-Star Game. He didn’t disappoint, as he went on to become one of the most honored defensive players of his time. He became a regular his rookie season and was named first- or second-team All-Pro every year from 1967 through 1973. He was All-NFL or All-NFC 1968 through 1973 and then All-NFC again in 1975. In 1971, he won the George Halas Award as the NFL's leading defensive player and was selected to play in six Pro Bowls (1969-1972, 1974, and 1975).

| Games Played: | ||

| Year | Team | Games |

| 1964 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1965 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1966 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1967 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1968 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1969 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1970 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1971 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1972 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1973 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1974 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1975 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1976 | Minnesota | 13 |

| 1977 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1978 | Minnesota | 14 |

| 1979 | Seattle | 16 |

| Career Total | 225 | |

| Additional Career Statistics: Interceptions: 1-1; Safeties: 2; Fumble Return for TD: 1 | ||

Championship Games

- 1969 NFL - Minnesota Vikings 27, Cleveland Browns 7

Eller was the starting defensive left end for the Vikings.

- 1973 NFC - Minnesota Vikings 27, Dallas Cowboys 10

Eller was the starting defensive left end for the Vikings.

- 1974 NFC - Minnesota Vikings 14, Los Angeles Rams 10

Eller was the starting defensive left end for the Vikings.

- 1976 NFC - Minnesota Vikings 24, Los Angeles Rams 13

Eller was the starting defensive left end for the Vikings. He recorded eight tackles, two assists, two sacks and one pass defensed.

- 1977 NFC - Dallas Cowboys 23, Minnesota Vikings 6

Eller was the starting defensive left end for the Vikings. He recorded one tackle, two assists, and one blocked PAT.

Super Bowls

- Super Bowl IV - Kansas City Chiefs 23, Minnesota Vikings 7

Eller was the starting defensive left end for the Vikings. He recorded three tackles and three assists.

- Super Bowl VIII - Miami Dolphins 24, Minnesota Vikings 7

Eller was the starting defensive left end for the Vikings. He recorded eight tackles.

- Super Bowl IX - Pittsburgh Steelers 16, Minnesota Vikings 6

Eller was the starting defensive left end for the Vikings. He recorded seven tackles and one assist.

- Super Bowl XI - Oakland Raiders 32, Minnesota Vikings 14

Eller was the starting defensive left end for the Vikings. He recorded three tackles and two assists.

| All-League Teams |

All-Pro: 1968 (PFWA), 1969 (HOF, PFWA, NEA), 1970 (AP, PFWA, NEA, PW), 1971 (AP, PFWA, NEA, PW), 1973 (AP, PW)

All-NFL: 1968 (AP, UPI, NEA, PW), 1969 (AP, UPI, NEA, PW)

All-Pro Second Team: 1967 (UPI, NEA), 1972 (AP), 1973 (PFWA)

All-Western Conference: 1968 (SN), 1969 (SN)

All-NFC: 1970 (AP, UPI, SN, PW), 1971 (AP, UPI, SN, PW), 1972 (SN), 1973 (AP, UPI, SN, PW), 1975 (AP, UPI)

All-NFC Second Team: 1972 (UPI), 1974 (UPI)

| Pro Bowls |

(6) - 1969, 1970, 1971, 1972, 1974*, 1975

* Did not play

| In the NFL Record Book |

(at time of his retirement following 1979 season)

• [3rd] Most Opponents' Fumbles Recovered, Career - 23

| Awards and Honors |

• 1970s All-Decade Team

| Year-by-Year team Records |

| Year | Team | W | L | T | Division Finish |

| 1964 | Minnesota Vikings | 8 | 5 | 1 | (2nd) |

| 1965 | Minnesota Vikings | 7 | 7 | 0 | (5th) |

| 1966 | Minnesota Vikings | 4 | 9 | 1 | (6th) |

| 1967 | Minnesota Vikings | 3 | 8 | 3 | (4th) |

| 1968 | Minnesota Vikings | 8 | 6 | 0 | (1st) |

| 1969 | Minnesota Vikings | 12 | 2 | 0 | (1st) |

| 1970 | Minnesota Vikings | 12 | 2 | 0 | (1st) |

| 1971 | Minnesota Vikings | 11 | 3 | 0 | (1st) |

| 1972 | Minnesota Vikings | 7 | 7 | 0 | (3rd) |

| 1973 | Minnesota Vikings | 12 | 2 | 0 | (1st) |

| 1974 | Minnesota Vikings | 10 | 4 | 0 | (1st) |

| 1975 | Minnesota Vikings | 12 | 2 | 0 | (1st) |

| 1976 | Minnesota Vikings | 11 | 2 | 1 | (1st) |

| 1977 | Minnesota Vikings | 9 | 5 | 0 | (1st) |

| 1978 | Minnesota Vikings | 8 | 7 | 1 | (1st) |

| 1979 | Seattle Seahawks | 9 | 7 | 0 | (3rd) |

Full Name: Carl Lee Eller

Full Name: Carl Lee Eller

Birthdate: January 25, 1942

Birthplace: Winston-Salem, North Carolina

High School: Atkins (Winston-Salem, NC)

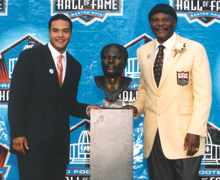

Elected to Pro Football Hall of Fame: January 31, 2004

Enshrined into Pro Football Hall of Fame: August 8, 2004

Presenter: Regis Eller, Carl's son

Other Members of Class of 2004: Bob Brown, John Elway, Barry Sanders

Pro Career: 16 seasons, 225 games

Drafted: 1st round (6th player overall) in 1964 by Minnesota Vikings; also selected in the 1st round (5th overall) of the AFL draft by the Buffalo Bills

Transactions: July 30, 1979 – Eller and No. 8 draft pick (1980 – Vic Minor, DB, Northeast Louisiana, 204th overall) traded from Minnesota Vikings to Seattle Seahawks in exchange for defensive tackle Steve Niehaus.

Uniform Number: #81, #71

Pro Football Hall of Fame Field at Fawcett Stadium

August 8, 2004

Regis Eller (presenter):

I cannot count the times growing up when I'd been introduced to someone, and the first thing they would say is, "Oh, you're Carl Eller's son." I'd always respond, "'Yes, but my name is Regis." Like many others sons of renowned people, I've tried most of my life to distance myself from simply being my father's son. To be recognized for myself.

However, when my dad honored me by asking me to be his presenter and give this speech, I started to think about who my father is and what I'm distancing myself from. I began to recall my childhood memories and what I believe are indicative of the Carl Eller I have been fortunate enough to call my father.

My dad taught me that it's OK to take risks, as evidenced by his acting career. He took risks whether it was on the field or on screen, but no one can say he lived his life by sitting on his hands. His filmography includes such films as Busting, Taggart and the Black Six. You haven't seen them? Me neither. They weren't exactly general release films. One of the funniest things is the parts that he tried out for but did not get. In such films as Throw Yo Momma From the Train. You know Meet Joe Black? It was originally Meet Black Joe starring Carl Eller. Of course, The Black English Patient. All great films, of course, but the credits and roles always listed him as "big black man." Obviously, they were roles that really tested him as an actor.

My dad didn't always take himself seriously, thank God, but he definitely took his roles in life seriously. My dad operated a drug treatment center for many years. And, I remember how important his clients and their sobriety were to him. As a kid I did not understand when my father would come home from work emotionally distraught and unable to interact with me. My mom would explain it. A client of my dad's rehab center who had been making good strides toward sobriety had inexplicably left the program prematurely. My dad would be visibly shaken in fear for the patient. Dad took this as a personal failure, and it resonated through him. However, he wore his disappointment on his sleeve because it was impossible for him not to. However, he would never give up, and he relentlessly attempted to get that client back into the program as if fighting for his own sobriety.

These instances prove to me that my dad does not live his life for himself, but rather an entire community revels in his accomplishments just as a whole community shares in his defeats. His work and care for people within his community is undoubtedly one of his life's works. As you will hear in a minute, I can proudly say my dad always tried to use his fame to affect meaningful change.

In my dad's early years with the Vikings, he purchased a home in north Minneapolis when most of his teammates were leaving the inner city for the suburbs. He elected to live in an underprivileged black neighborhood and still lives there today.

My dad always told me, "Son, you have to give back." And if you talk to people in north Minneapolis today, you will unquestionably hear a story about how Carl Eller has helped them or someone they know and what it means to have Carl Eller as a part of their community. As caring as he was with the people he tried to help, he was even more so with his children.

I remember dad surprised me with tickets to the Twins game. On our way back from the game, a woman ran a red light and hit us directly on my side. The first memory I have of that accident is my dad holding my hand telling me everything was going to be all right. But I could see in his eyes how scared he was for me and how badly he wanted to take my pain away. He didn't leave my side the night I was in the hospital or for the next two weeks. I'll never forget that day. It is the day I truly learned of his love for me and he shows the same affection with all his children. He has given me a vision of the caring a father should give his son and a vision of the father I want to be and everyone should have.

So, when I think of who my dad is, I realize he is all these things. The struggling actor, the passionate drug rehab counselor, the good citizen, the consummate father, and yes, the football player. So, today, if someone asked me, "Aren't you Carl Eller's son?" instead of saying, "Yes, but ...," I say, "Yes, yes I am. And, my name is Regis."

Dad, congratulations on a well deserved honor. Thank you for the opportunity to pay tribute to you. And, also, thanks for everything.

Dad, congratulations on a well deserved honor. Thank you for the opportunity to pay tribute to you. And, also, thanks for everything.

Carl Eller

They keep saying it's going to get better, but Regis, it can't get any better than that. Thank you, son. Thank you. Today I'm going to talk about being a winner. But, before I start, I'd like to say a little prayer.

Father, guide my thoughts and words in this glorious day the Lord has made. Stand by my family and me; keep us close to your heart during this – my finest hour. Amen.

My name is Carl Eller and I grew up in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. I’m proud to say I grew up with really super parents, great parents. They were decent, honest, working, hard-working family. But, we were poor and we worked for everything we got. I'm very, very proud to be part of that family. But growing up in Winston-Salem, it was kind of a town where I think, like many towns, the neighborhood I grew up in, there weren't a lot of people running around talking about, "I'm going to be a professional football player" or they didn't really have a lot of dreams. Mostly, it was going from day to day and people were trying their best to earn a living. And there weren't a lot of dreams. I suppose if people really had dreams if they were lucky, they might grow up and get a job in their local factory. That was kind of a great ambition of many people, and it was a great one. But, I really didn't start off with any dreams or any goals. I was just a really happy kid running around, and in of all places, Happy Hill, North Carolina.

My father died when I was young, and of course I was angry and full of negative behavior. My high school principal suggested that I take all of that negative energy and use it out on the football field. You know, one of the eeriest things that happened since I was inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame – I got a call from my high school football coach. And, I say eerie because here is somebody that knew me before I even knew what football was. And now I'm going into the Pro Football Hall of Fame. You know, I said in the beginning that I didn't really have any goals or I really didn't have any dreams. I really didn’t until I met my high school football coaches, Ben Warren and Warren Oldham, and they started to talk about the possibilities through the sport of football, but I had to certainly make some changes with my negative behavior. And they began to believe in me and began to make me believe in myself.

I had a lot of teachers that believed in me, but I certainly have to tell you that not all of them did. But football did give me hopes and dreams, and I began to set goals for myself, and through that my goal was always to be the best and I always gave my all. Football was great. It was a wonderful arena in which I could use all of my God-given skills. It was a perfect match. Football began to pay off early; it gave me a scholarship to college, and it continued to pay off as I began to earn a wonderful living and raise a family doing what I love.

Now I look and I ask, "To what do I owe this honor? To what do I owe this great hour?" I am grateful to many, many people and, of course, I have to start with my family – all of them, my entire family. But, I want also to thank people like Murray Warmath, who recruited me to the University of Minnesota, and the University of Minnesota itself – a great, great institution. Then, of course, there's Max Winter, the owner of the Minnesota Vikings. And Norm Van Brocklin, my first coach. Then, Bud Grant, of course, the coach which we rose to stardom as the Minnesota Vikings and the "Purple People Eaters." And, of course, the National Football League. What a great arena, what a great opportunity to be part of the National Football League.

But my question is, "What can I do with this great honor?" I could say, "I earned it; I waited all these years. I can do with it what I want." But, that would be a sad and a big mistake. It's because the gentlemen sitting behind me are role models and I've gotten to know them as role models, and they're great. They're an excellent group of men, and I'm very, very proud to join them on this day. I believe that all professional athletes and college athletes are role models or, at least, they should be.

My first role model was a young man by the name of Norman King. He was an athlete going to Winston-Salem State College, and he came by my house one day. And our house is bordered by a fence about chest high. He just leaped right over that fence. He was an impressive guy because he had on his athletic warm-up gear, and I thought how different this young man is from the rest of the people in my community. He had goals and he had challenges, and he was already on his way in college. And I thought, "What a great guy. What a great person to be."

I have a question, and I asked a question: "To what do I owe this great honor?" And it's a good one. What can I do with this great honor of being inducted to the Football Hall of Fame Class of 2004? My answer is that I want to use this platform to help young African American males to participate fully in this society.

I know that we must give young African American men a message that will lead them in the direction differently from where many of them are headed today. I want that direction to be headed toward the great universities and colleges of our nation, not to the prisons and jail cells.

African American young men, as well as young women, must know that they are part of the establishment and not separate from it. That they are part of this great America. They must know that there parents and grandparents and their grandparents' parents before them helped build this great country. And parents, yes, we do have a great challenge before us – maybe the greatest in history –and that is that we must teach our kids the value and importance of education, teach them to be members of this society, to participate fully and have a respect for country, laws and customs. Show them that if they want this country to do the right thing that we must do the right thing and to teach our children to be actively involved in everything that's going on in this country.

Barack Obama is a fine young man and a great example. But he is not unique. Contrary to what we see in our media-controlled establishment – we're in a media-dominated society, which has focused on the negative in the African American communities and other communities of color – there are hundreds, if not thousands, Barack Obamas out there.

We must educate our children. That's the paramount challenge. We must give our children books, but first we must know what books to give them. Books that help them understand our economy, books on technological and scientific and biological advancements being made every day. Books on relationships, not just with each other but on our foreign neighbors. And certainly books on how to participate in our political system.

I promise young men and women, and I specifically say again to African American males, because it seems that our country has turned its back on you. And it seems that some areas have even given up hope. I am here today to say I haven't given up on you. And you need to know because I know that you have the talent, you have the intelligence and now you have the opportunity to make right of this great occasion. And I'm calling on you now to do the right thing.

Don't let all the hard work your forefathers have done to make this a great country go to waste. Young men of African American descent, hear me now. It breaks my heart, and it breaks all of our hearts. This is not the future your forefathers have built for you. This is not the future that we fought for in the '50s, and '60s and '70s. What breaks our heart is to see you involved in gangs and selling drugs and killing each other. That breaks our hearts.

We put our lives on the line so that you could enjoy the freedoms that we enjoy today. We put our lives on the line yesterday so that someone – there could be a Barack Obama today. And there could be a Carl Eller today. And there could be other Hall of Famers sitting before you today.

So now I stand here and say to you, if the future of America is to be strong, you must be strong. You must hear the cries of our forefathers and pick up the fight that has helped to make this country great and helped make it what it is today.

Know that you are loved and respected and we have high hopes for you – maybe higher than what you imagine. But if this country is to be a winner, you are to be a winner. To be a winner takes two things, and I think those two things are courage and commitment. It takes courage to be a winner. If you have courage, you can overcome, you can conquer fear and you can conquer despair. And you must be committed to your goals and to your cause. And commitment means being bound to a course of action – spiritually, emotionally and intellectually. These two things separate the winners from the losers. And you must be a winner. not losers.

And you can tell the winners from the losers. Here's how you can tell the winners from the losers: The winner is always part of the answer; the loser is always part of the problem. The winner always has a program; the loser always has an excuse. The winner says, "Let me do it for you." And the loser says, "Uh-uh; it's not my job." The winner sees an answer for every problem, and the loser sees a problem in every answer. The winner sees a green near every sand trap; the loser sees two or three sand traps near every green. The winner says, "It may be difficult, but it is possible." And, the loser says, "It may be possible, but it's too difficult."

Ladies and gentlemen, young men, young ladies, especially the young men that I'm talking to: Be the winners. Be the winners!

God bless you. Thank you very much. Thank you.